Archives

now browsing by author

The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

The moon is full tonight ….

It’s as full as it was

in that poem by Coleridge

where he carries his year-old son

into the orchard behind the cottage

and turns the baby’s face to the sky

to see for the first time

the earth’s bright companion,

something amazing to make his crying seem small.

And if you wanted to follow this example,

tonight would be the night

to carry some tiny creature outside

and introduce him to the moon.

And if your house has no child,

you can always gather into your arms

the sleeping infant of yourself,

as I have done tonight,

and carry him outdoors,

all limp in his tattered blanket,

making sure to steady his lolling head

with the palm of your hand.

And while the wind ruffles the pear trees

in the corner of the orchard

and dark roses wave against a stone wall,

you can turn him on your shoulder

and walk in circles on the lawn

drunk with the light.

You can lift him up into the sky,

your eyes nearly as wide as his,

as the moon climbs high into the night.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

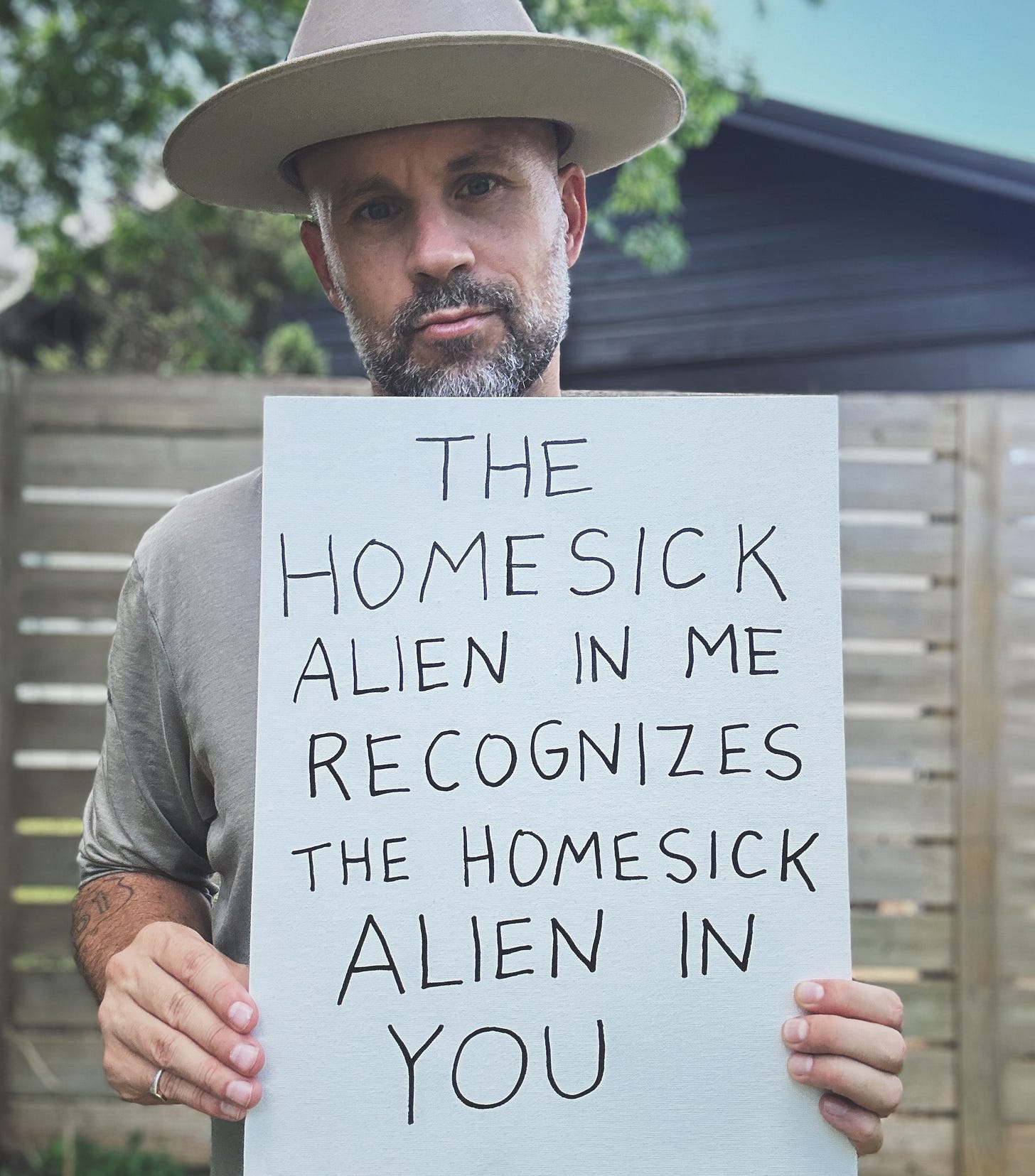

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.

What you held in your hand,

what you counted and carefully saved,

all this must go so you know

how desolate the landscape can be

between the regions of kindness.

How you ride and ride

thinking the bus will never stop,

the passengers eating maize and chicken

will stare out the window forever.

Before you learn the tender gravity of kindness

you must travel where the Indian in a white poncho

lies dead by the side of the road.

You must see how this could be you,

how he too was someone

who journeyed through the night with plans

and the simple breath that kept him alive.

Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

you must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore,

only kindness that ties your shoes

and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread,

only kindness that raises its head

from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking f

and then goes with you everywhere

like a shadow or a friend.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

In the usual iconography of the temple or the local Wok

you would never see him doing such a thing,

tossing the dry snow over a mountain

of his bare, round shoulder,

his hair tied in a knot,

a model of concentration.

Sitting is more his speed, if that is the word

for what he does, or does not do.

Even the season is wrong for him.

In all his manifestations, is it not warm or slightly humid?

Is this not implied by his serene expression,

that smile so wide it wraps itself around the waist of the universe?

But here we are, working our way down the driveway,

one shovelful at a time.

We toss the light powder into the clear air.

We feel the cold mist on our faces.

And with every heave we disappear

and become lost to each other

in these sudden clouds of our own making,

these fountain-bursts of snow.

This is so much better than a sermon in church,

I say out loud, but Buddha keeps on shoveling.

This is the true religion, the religion of snow,

and sunlight and winter geese barking in the sky,

I say, but he is too busy to hear me.

He has thrown himself into shoveling snow

as if it were the purpose of existence,

as if the sign of a perfect life were a clear driveway

you could back the car down easily

and drive off into the vanities of the world

with a broken heater fan and a song on the radio.

All morning long we work side by side,

me with my commentary

and he inside his generous pocket of silence,

until the hour is nearly noon

and the snow is piled high all around us;

then, I hear him speak.

After this, he asks,

can we go inside and play cards?

Certainly, I reply, and I will heat some milk

and bring cups of hot chocolate to the table

while you shuffle the deck.

and our boots stand dripping by the door.

Aaah, says the Buddha, lifting his eyes

and leaning for a moment on his shovel

before he drives the thin blade again

deep into the glittering white snow.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

In the event that you wake up

and find your soul separated from source

and manifest into material form, don’t panic.

Your condition is only temporary.

You have been selected for the opportunity

of human incarnation.

This 3D simulation is designed

to break up the monotony of eternity

by giving you a fully immersive experience

as a distinct ego identity.

Your body will serve

as your physical avatar

as you navigate a dense and dramatic reality.

There will be many distractions

causing you to forget your true nature and origin.

You will experience a range of emotions

from joy to loneliness to despair.

But remember – no matter

what trials and traumas you encounter,

your soul remains perfectly safe.

At times you may feel lost or afraid.

This is totally normal.

If you ever need guidance,

simply slow down your busy mind

and bring your awareness

to the quiet place

inside yourself.

On this planet, nothing is permanent.

People and things will come and go.

You will fall in love and form sentimental attachments

only to lose everything you hold dear.

So cling to nothing too tightly, even yourself,

and when it’s time to let go, let go with grace,

for nothing is owned, only borrowed.

As you walk among

the people on the planet,

try to be a good guest.

Tread lightly. Remember

that you are only visiting.

Don’t make a mess.

Listen more than you speak.

Give more than you take.

Don’t keep your soft heart

locked inside a glass cage,

protected from wear and tear.

You’ll never make it out alive

and time passes quickly.

So come back with some battle scars

and good stories to tell.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

Epistle

There are these elements and aspects of the sand painting that is my life:

Work, friendship, worship, love, sex, loss, women, men, Maia, my family,

Political questions, ethics, values, investment, expectation, reward,

Success, failure, accomplishment, mastery, longing, joy,

Engagement, stimulation, trepidation, the Word itself,

Fear, habit, breath, death, health, running, eating, other bodily functions,

Music, counting money, trying hard, not trying at all, giving a damn,

Being open, being hurt, helping, the unknown,

Housecleaning, laundry, dishes, cooking, shopping, driving,

Arranging baby sitters, writing, reading, shaving and showering,

Weighing myself, making love, talking to crows,

Seeing butterflies, horses, turtles, and birds in profuse array,

flying, scurrying, or dead in the highway.

I live my life.

I pay the bills.

I remember always the vast mystery I participate in,

This vast liveliness, this immense universe where goodness abounds,

Where illness, injury, depression, pain, and death stalk everyone inevitably.

Where by the greatest of luck, and some effort, I walk

my current, common, narrow, blessed, simple, single path.

Where hope, fear, fantasies, and realities whisper breezily about me.

Where time passes slowly and in the wink of an eye.

Where love that is strong one moment is faded the next.

The nonstop changing that I hold onto, adjust to, anticipate and hallucinate.

This is the peeling birch bark, snakeskin shedding, noon whistle time.

Understanding evolves. Understanding is illusion.

I am momentary. pleased, cautious, strong, ambitious, quixotic, romantic,

Thankful, awestruck, blissful, present, past, and future,

Changeless and forever, daily, divine, and never,

Before me, after me, regardless of me and mine.

We pause in the stream of life

The waters are rushing swiftly

We touch, smile at, and puzzle one another

We struggle against the current,

We follow the path of least resistance.

We are none of us the Grand Canyon, nor the Colorado River.

I have had occasion to love you.

November, 1976

POETRY

- 99 Gratitudes in 3 Minutes – A Yoga Chanting Poem

- A Poem is Born

- After The News

- Alan

- Alan Is Dead

- American Wedding, 2011

- Ask the Sphinx – 2 approaches

- Baggage Claim

- Beach Plum Jam

- Beau Dies

- between spiders

- Beyond the Fishermen

- blood

- Burnt Wood – for Bubi

- Cheerio Box Speaks of Love

- Conversation With A Ladle

- Coyote in the Headlights

- Coyote in the House

- Crow’s Songs

- Daybreak

- Death Factories

- Death of the Dolphin

- Epistle

- Flautist – inspired by George and Ira Gerswin

- Furry Bug

- Gospel of the Redwoods

- Homage to an Unattractive Woman

- Honored

- Insects in Amber

- It: In Honor of Dr. Seuss

- Journey to Standing Rock

- Kevin Garnett in Africa

- Life among the barbarians

- Long ago, perhaps yesterday

- Mandalay Hills

- Meeting the Dead Poet

- Mesquite Dunes

- Miles’ Ashes

- Miles’ Journey

- My First Yoga Teacher

- One Drop of Rain

- Salton Sea

- Self Love

- She Has Loved 100 Men

- Shivering in Majesty

- Sunrise

- The Furry Bug

- The Love Life of Clams

- Throwing Away

- Turn up for Turnips – a song

- Uncle Sol

- What The Stones Say

- when spring arrives ice flows out of the bay

- Whispering Among The Gods

- Willow

- Winter Fog

- Work and Love are What Really Matter: a reunion poem for the BHS class of 1958 reunion

How She Heard It – Todd Davis

Your father gathered what was left

after the birth, slick sack of salt

and blood coloring his hands

warm from my body. He couldn’t help

that it felt the same as when I took him

inside me, drew him out of himself

to be joined with what we were making.

At the edge of our small orchard

he settled the plum seedling

he’d started three years before,

snugged roots in the hole to eat

the placenta. The part of you

you didn’t need fed the tree,

and when you turned six,

you ate from the branches.

Your small hands clasping the dark

shiny skin as you bit the saffron flesh,

juice dribbling at chin, smell as sweet

as the sugar you were born in.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

No, no, there is no going back.

Less and less you are

that possibility you were.

More and more you have become

those lives and deaths

that have belonged to you.

You have become a sort of grave

containing much that was

and is no more in time, beloved

then, now, and always.

And so you have become a sort of tree

standing over a grave.

Now more than ever you can be

generous toward each day

that comes, young, to disappear

forever, and yet remain

unaging in the mind.

Every day you have less reason

not to give yourself away.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

Put down that bag of potato chips, that white bread, that bottle of pop.

Turn off that cellphone, computer, and remote control.

Open the door, then close it behind you.

Take a breath offered by friendly winds. They travel the earth gathering essences of plants to clean.

Give it back with gratitude.

If you sing it will give your spirit lift to fly to the stars’ ears and back.

Acknowledge this earth who has cared for you since you were a dream planting itself precisely within your parents’ desire.

Let your moccasin feet take you to the encampment of the guardians who have known you before time, who will be there after time. They sit before the fire that has been there without time.

Let the earth stabilize your postcolonial insecure jitters.

Be respectful of the small insects, birds and animal people who accompany you.

Ask their forgiveness for the harm we humans have brought down upon them.

Don’t worry.

The heart knows the way though there may be high-rises, interstates, checkpoints, armed soldiers, massacres, wars, and those who will despise you because they despise themselves.

The journey might take you a few hours, a day, a year, a few years, a hundred, a thousand or even more.

Watch your mind. Without training it might run away and leave your heart for the immense human feast set by the thieves of time.

Do not hold regrets.

When you find your way to the circle, to the fire kept burning by the keepers of your soul, you will be welcomed.

You must clean yourself with cedar, sage, or other healing plant.

Cut the ties you have to failure and shame.

Let go the pain you are holding in your mind, your shoulders, your heart, all the way to your feet. Let go the pain of your ancestors to make way for those who are heading in our direction.

Ask for forgiveness.

Call upon the help of those who love you. These helpers take many forms: animal, element, bird, angel, saint, stone, or ancestor.

Call your spirit back. It may be caught in corners and creases of shame, judgment, and human abuse.

You must call in a way that your spirit will want to return.

Speak to it as you would to a beloved child.

Welcome your spirit back from its wandering. It may return in pieces, in tatters. Gather them together. They will be happy to be found after being lost for so long.

Your spirit will need to sleep awhile after it is bathed and given clean clothes.

Now you can have a party. Invite everyone you know who loves and supports you. Keep room for those who have no place else to go.

Make a giveaway, and remember, keep the speeches short.

Then, you must do this: help the next person find their way through the dark.

***

Joy Harjo was born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1951, and is a member of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation. She is the author of several books of poetry, including An American Sunrise, and Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings. She was the United States poet laureate from 2019-22 the dark.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin

Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

This is what you shall do;

Love the earth and sun and the animals,

despise riches,

give alms to every one that asks,

stand up for the stupid and crazy,

devote your income and labor to others,

hate tyrants,

argue not concerning God,

have patience and indulgence toward the people,

take off your hat to nothing known

or unknown

or to any man or number of men,

go freely with powerful uneducated persons

and with the young

and with the mothers of families,

read these leaves in the open air every season

of every year of your life,

re-examine all you have been told

at school or church or in any book,

dismiss whatever insults your own soul,

and your very flesh shall be a great poem

and have the richest fluency not only in its words

but in the silent lines of its lips and face

and between the lashes of your eyes

and in every motion and joint of your body.

Poetry

- A Dog Has Died by Pablo Neruda

- A Moment of Silence – by Emmanuel Ortiz

- A Quiet Life – Baron Wormser

- A Wreath to the Fish – Nancy Willard

- Alone – Jack Gilbert

- Be Kind, Rewind – Neil Silberblatt

- Black Momma Math – Kimberly Jae

- Combat Primer – Charles Bukowski

- Crow Blacker Than Ever – Ted Hughes

- Dismiss Whatever Insults Your Own Soul – Walt Whitman

- Don’t fall in love with a woman who reads – Martha Rivera-Garrido

- Failing and Flying – Jack Gilbert

- Feel Mo – Michael Korson

- Footprints In Your Heart – Eleanor Roosvelt

- For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet – Joy Harjo

- Forgetfulness – Billy Collins

- Growing Old – Emma Rosenberg

- Homesick: A Plea for Our Planet – Andrea Gibson

- How She Heard It – Todd Davis

- How to Slay a Dragon – Rebecca Dupas

- I Talked to a Lady – Tanya Howden

- If You Knew – Ellen Bass

- Instructions before visiting Earth – James McCrae

- KINDNESS – Naomi Shihab Nye

- Love is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay

- Men – Maya Angelou

- my brain and heart divorced ~ john roedel

- Ode to Those Who Block Tunnels and Bridges – Sam Sax

- Relax – Ellen Bass

- Shoveling Snow With Buddha – Billy Collins

- Sleeping in the Forest – Mary Oliver

- Small Stack of Books – Blake Nelson

- Soliloquy of the Solipsist – Sylvia Plath

- Tangled Up In Blue – Bob Dylan

- The Four Noble Truths – Jake Onami Agnew

- The History of One Tough Motherfucker – Charles Bukowski

- The Layers – Stanley Kunitz

- The Long Boat – Stanley Kunitz

- The Moon is Full Tonight – Billy Collins

- The Shyness – Sharon Olds

- The War Works Hard – Dunya Mikhail

- There Is No Going Back – Wendell Berry

- To Diego with Love – Frida Kalko

- Tryst with Death – Gina Puorro

- Two-bloods – Rolando Kattan

- Wage Peace – Mary Oliver

- War Primer – Bertholt Brecht

- What I Learned From Listening to a Stutterer – Ellen Zorin